Cleveland's First Waterworks

In 1850, at the behest of Mayor William Case, Cleveland City Council appointed a committee to address the issue of providing a sufficient supply of “pure water” for the city’s growing population. At the time, all of Cleveland’s drinking water came from springs, wells, canals, and the Cuyahoga River.

Following two years of research, the committee delivered a report to the Mayor and Council in November 1852 detailing its recommendations for the construction of a public waterworks system that would provide water for all of the city’s needs. The report pointed out how such a system would improve the health and quality of life for residents across the city by providing clean, accessible water for drinking, cooking, cleaning, and fire protection.

The committee also recommended that City Council hire Theodore Scowden, the engineer who had designed Cincinnati’s waterworks, to design Cleveland’s new system. Shortly thereafter, Scowden was at work as the Engineer for the City’s Water Works Board.

In 1853, Scowden submitted a report to City Council with his recommendations for the design of the new Cleveland waterworks system. The facility Scowden recommended, and ultimately constructed following state and local approval for the financing, consisted of a pump station, a 6-million-gallon reservoir, 11 miles of water mains including one beneath the Cuyahoga River, and a water intake located 300 feet out into Lake Erie and just west of the mouth of the Cuyahoga River. In his report, Scowden estimated the initial cost for such a system at $381,000, equivalent to roughly $13.5 million today.

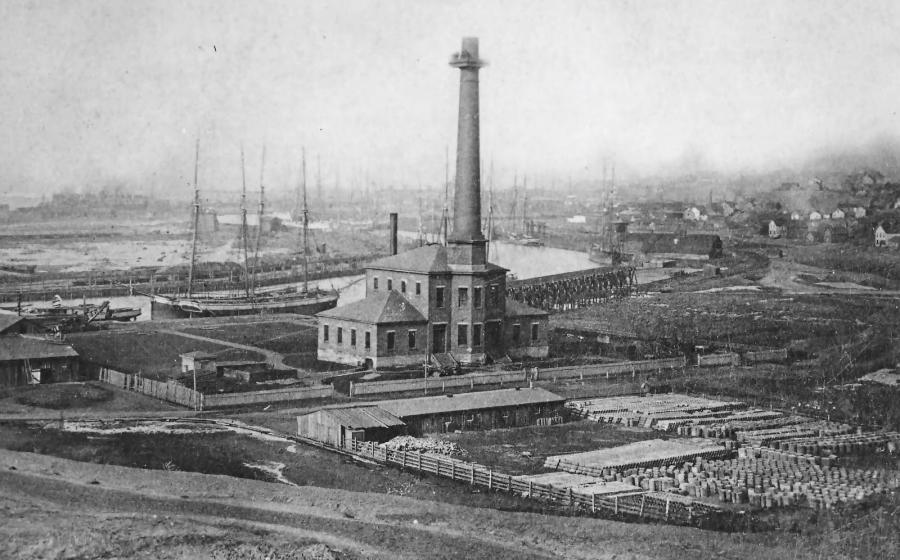

Scowden determined that a location west of the Cuyahoga River would be ideal for the pump station and reservoir as the elevation was slightly higher than on the east bank and coal for powering the facility could be delivered directly by railcar. However, construction proved to be much more challenging than anticipated due to the swampy nature of the land on the west bank of the river. It required 14 feet of excavation accomplished by five steam engines before finding ground stable enough for the pump station foundation.

The pump station was located on Division Street, the site of the current Garrett A. Morgan Water Treatment Plant, and housed two Cornish engines, the first introduced west of the Allegheny Mountains. The building was left open so people could watch the steam-powered, 70-inch engines work.

The reservoir was constructed between Franklin Blvd. to the north, Duane St. (now West 32rd) to the east, Woodbine Ave. to the south, and Kentucky St. (now West 38th) to the west, an area covering approximately 6 acres. The base of the reservoir covered 4 acres and measured 332 feet by 466 feet. Built of earthen embankments and lined with an impervious clay puddle and hard-burnt brick laid in hydraulic mortar, the trapezoid-shaped reservoir held 6 million gallons of water in two compartments separated by an earthen retaining wall.

Steps up the side of the reservoir led to a gravel walkway around the perimeter. The "reservoir promenade" was a popular place for the public to gather and enjoy the scenic view from atop the highest man-made structure in the city at the time.

In anticipation of the Ohio State Fair being held in Cleveland in September 1856, a large stone fountain was constructed at the center of Public Square that would be fed with water from the reservoir. On September 24, 1856, the fountain, and Cleveland Water, officially went into operation.

As Cleveland grew throughout the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Scowden’s original facility would be replaced by a newer and larger water treatment plant. And the Kentucky St. reservoir would be converted into a park that is now Fairview Park and Kentucky Gardens. The original pump station is now the site of the Garrett A. Morgan Water Treatment Plant (one of four in Cleveland Water’s system) which pumps an average of 60 million gallons of water a day to the residents and businesses of Cleveland and beyond.

References: Cleveland Historical, Encyclopedia of Cleveland History, and Documentary History of American Water-works